Why sharing Cali's story?

As an amateur and then professional rider, I evolved for several years on show jumping circuits and in high-level stables. At the time, I had never heard of the equine atypical myopathy (EAM), a poisoning caused by the samaras and seedlings of sycamore maples.

Unfortunately, I had to face it brutally with my young horse Cali, four years old at the time of the incident, in 2016. Cali was one of the 25% of horses who survived this poisoning¹. Until then, veterinarians had a 75% failure rate when treating this disease.

A heartfelt thank you to Dr Dominique Marie Votion and the ULiège team for sharing information on atypical myopathy to try to better understand the disease.

I wanted to share our story so that rider-owners are better informed about this terrible intoxication and can act consequently.

¹ Leaflet « myopathie atypique : comprendre pour mieux prévenir », IFCE 2017

Comments from Dr Dominique Votion :

« I accepted with pleasure to read and comment (in green) the first part of this writing. This one engages only its author but I wish to underline the positive will of the latter to transmit her feelings and her journey to others who would be confronted with the same situation. »

What is the equine atypical myopathy (EAM)?

EAM is a severe poisoning caused by samaras, those flying seeds that we commonly call "helicopters", and the seedlings of sycamore maples (Acer pseudoplatanus). If they are ingested by the animal, the toxins present in them "attack" the postural, respiratory and cardiac muscles of equines and can lead to death, alas in the majority of cases, within 48 hours. Before its discovery in 2014, the cause of EAM was the subject of much questioning and many equestrians were helpless in the face of this disease. Since there is no cure for EAM yet, prevention is key!

“The sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) is implicated in European cases of atypical myopathy while the negundo maple (Acer negundo) is recognized as the cause of this disease in the United States of America”, as indicated in the review article (François et al., 2020) freely available via the QR code below and published in open access in the journal Animals, in 2020.

This article, which I will quote regularly, is entitled “Answers to frequently asked questions (FAQs) about the feeding and management of equines and the management of pastures to reduce the risk of atypical myopathy”.

EAM is linked to grazing and occurs in autumn and spring following the ingestion of seeds and seedlings of the trees mentioned above. “The ingestion of seeds called samaras or seedlings of the incriminated trees is accompanied by the ingestion of two cyclopropyl-amine acids: Hypoglycin A (HGA) and methylene-cyclopropyl-glycine (MCPrG). The maples commonly present in Europe such as the Norway maple (Acer platanoides) or the field maple (Acer campestre) do not contain these compounds, unlike the sycamore maple.”

The toxicity of HGA and MCPrG is not due to these molecules by themselves but by their toxic metabolites: respectively, methylenecyclopropylacetyl-CoA (MCPA-CoA) and methylenecyclopropylformyl-CoA (MCPF-CoA): “These inhibit certain enzymes responsible for the beta-oxidation of fatty acids and therefore the production of energy via lipid metabolism. The clinical signs of this poisoning are an acute rhabdomyolysis syndrome uncorrelated with the performance of physical effort. This clinical picture can be observed in several horses of the same group. In more than 50% of cases, the following clinical signs are observed: weakness, decubitus, myoglobinuria, distended bladder, muscle tremors or fasciculation, reluctance to move, sweating, normothermia and congested mucous membranes.”

COMMENTS FROM ULiège : Research is underway to try to understand the exact involvement in the pathological process of the toxic molecules, HGA and MCPrG, produced by certain maple trees. To date, only HGA and MCPrG have been associated with atypical myopathy. However, other potentially toxic molecules are produced by these same trees. Research is also interested in identifying and studying the action of these other molecules.

How to recognize the trees incriminated in the EAM?

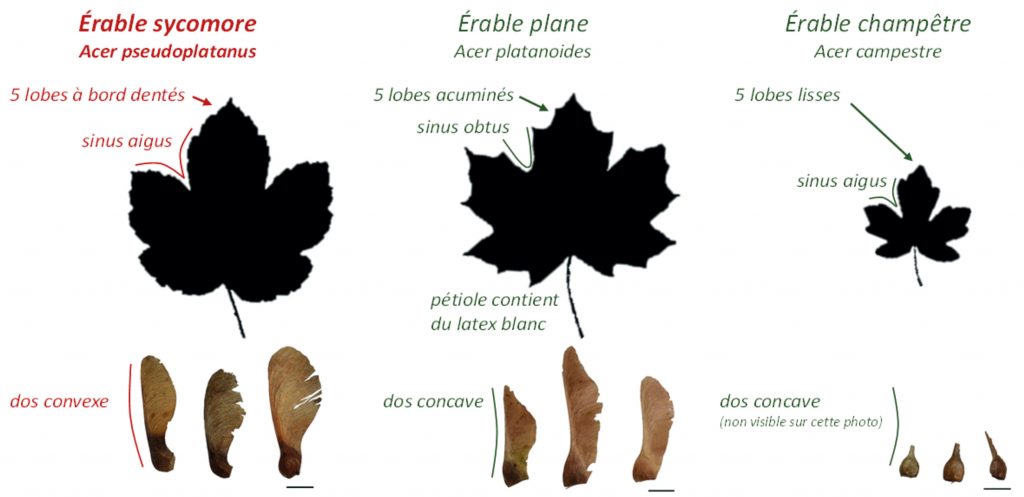

The sycamore maple leaf has five tooth-edged lobes with acute sinuses. The samaras are worn in pairs forming an acute angle. In contrast, the leaves of Norway maple (a non-toxic tree) have five pointed acuminate lobes with obtuse sinuses. The samaras are worn in pairs forming an obtuse angle. The leaves of the field maple (a non-toxic tree), on the other hand, have five smooth lobes with acute sinuses. They are smaller than the leaves of sycamore and plane maples. Samaras are worn in pairs forming a flat angle.

How to prevent contact with these toxins?

Contrary to what one might think, it is unfortunately not enough to simply check that a pasture does not contain between its lists one or more sycamore maple(s). “Depending on climatic conditions (wind and rain, editor’s note), maple samaras are capable of dispersing up to several hundred meters”, resumes the article on the management of equines and pastures facing the EAM, published in Animal magazine. “Consequently, the contamination of pastures with samaras or seedlings is not necessarily linked to the presence of a tree on the pasture. At the beginning of autumn and especially during strong winds, the sycamore samaras can disperse. […] Spreading manure and/or harrowing meadows also increases the risk by dispersing toxins. With regard to prevention at pasture level, there is an interest in eliminating seedlings. It should be noted, however, that after mowing or applying a herbicide, the seedlings still contain HGA… These techniques are therefore ineffective in destroying the toxic material of the plant.”

COMMENTS FROM ULiège : Mowing and spraying (with suitable products) are effective in “killing” seedlings, but mowed or sprayed plant material still contains the toxins responsible for atypical myopathy. It is therefore necessary to wait until this material is completely degraded to consider that it is no longer toxic.

The water also needs to be monitored. “A 2019 study (by Renaud et al.,) showed that HGA is released into the water by the flowers of Acer pseudoplatanus when they are immersed in them and also by the samaras if the latter are altered. The administration of water to horses in pasture via a bathtub placed under a sycamore maple tree or collecting water from the roof or even via a natural watercourse could therefore contribute to the poisoning of horses. Although there is currently no published study on the stability of HGA in water; the administration of drinking water to horses via the traditional distribution network, during periods of risk (i.e. autumn and spring) is to be preferred.”

In conclusion, what can we learn from this disease? “Given that there is not yet a cure for EAM, prevention remains the key”, insist the authors of the article. “In order to reduce the risks, it is advisable to avoid wet meadows, permanent grazing, harrowing of pastures and proximity to sycamore maple. During periods of risk, grazing time should be modulated according to climatic conditions and limited to less than six hours per day. Grazing horses should receive supplemental feed preferably with feed containing vitamin B2 (ie riboflavin) such as alfalfa. Where hay or silage is distributed, caution should be exercised in ensuring that the forages are free of toxins. It is also advisable to provide a block of salt and water from the distribution network. It should be noted that EAM is an emerging disease and equines of any age and any pasture with a nearby sycamore tree should be considered at risk. These preventive measures should be implemented for a period of three months twice a year, starting in March for “spring cases” and then again in October to avoid “autumn cases”.”

Part 1

Sudden confrontation with the disease

Cali, my young four-year-old horse at the time, has been on pasture for ten days, which he shares with six other horses. Access to hay is governed by the dominant of the herd but, my horse is not losing weight, I am not particularly worried about it. I also provide Cali with a food supplement at each visit and therefore take care of his diet.

COMMENTS FROM ULiège : Feed intake (hay, straw, complete mix, oats, barley and/or corn) throughout the year decreases the risk of atypical myopathy. Be careful, the hay may contain samaras and sycamore maple seedlings which remain toxic in the hay even after several months or even years of storage. It is therefore recommended not to produce hay, haylage and/or silage on the parts of the plots at the edge of the forest and overhung by sycamore maples. Toxin-free fodder can therefore be given ad libitum, but it should not be placed directly on the ground under the maples, at the risk of contamination by samaras falling from the trees or by emerging seedlings.

It is the morning of December 17, 2016 and I immediately notice that my horse is not well: he is listless, sweats profusely, breathes heavily, carries his head towards the ground and has bright red mucous membranes. Her rectal temperature is 36.2°C. While waiting for the arrival of the veterinarian called in the process, I try to make Cali eat, which he accepts but with difficulty. He’s dehydrated – his skin won’t come back when I pinch him – and he gurgles a lot. I note on the ground the presence of seeds in the shape of “helicopters” but am still in denial and panic.

The vet arrives forty-five minutes later. He quickly suspects equine atypical myopathy and informs me that Cali’s vital prognosis is engaged. Cali is immediately perfused in the meadow and receives two infusions of 5L each – to which are added 20mL of Biodyl² –, as well as syringes of charcoal and clay, slipped between his lips.

Intravenously, the veterinarian administers 10 mL of Mefiosyl³, an anti-inflammatory. Cali’s urine is a walnut color. The veterinarian confirms the EAM, takes a blood sample, and goes to the clinic. The horse is not transportable in a van but we have to take it to the nearest box, two hundred meters away…. It took us two hours of effort to get there. Cali is exhausted but finally warm.

COMMENTS FROM ULiège : There is no antidote to the toxins responsible for atypical myopathy, so treatment is symptomatic: it essentially aims to ensure vital functions, manage suffering and facilitate the elimination of toxins. Blood tests and visualization of urine (coffee color) help to reinforce the diagnosis of atypical myopathy.

² Biodyl™ is an injectable solution used in the prevention and treatment of selenium deficiency states, such as myopathy and muscular dystrophy. Source: ANSES (National Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health Safety).

³ MefiosylTM is prescribed for the treatment of inflammation and pain relief in muscular and skeletal conditions, particularly in the case of colic. Source: ANSES (National Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health Safety).

The beginning of the treatment

On the second day, Cali is becoming more and more absent. His head is low and his lips, nostrils and salt shakers visibly swell. He’s bloated and waterlogged from the twelve infusions we’ve been injecting him continuously since the day before. To reduce the phenomenon of water retention, we tie his head up. Cali is unresponsive, his whole body is heavy and sagging. Not being able to do anything more for him, I give myself a brief break and leave the supervision to my husband. When I return, he informs me that Cali has muscle spasms: the ears lean against the neck, the neckline is hooded and his eyes twitch with each contraction. I urgently call the veterinarian, terrified at the idea that this crisis of tetany will make him suffocate.

When he arrives, the veterinarian hesitates: he considers euthanasia but keeps a slim hope, since Cali is still standing, has stopped the spasms, and seems to want to hold on despite everything. When he left, the vet gave me a 50mL syringe of Dexadreson⁴, with instructions to use it if my horse was in too much pain. We continue our watch. My heart leaps at every sign of foreleg weakness. I manage to make Cali swallow a few bits of carrot, which I slip between his lips.

⁴ Dexadreson™: Injectable Dexamethasone solution, used as a powerful synthetic glucocorticoid. Source: MSD Animal Health.

Part 2

A slow healing full of pitfalls

On the morning of the third day, Cali eats crushed apple and carrot bits, I’m overjoyed! I also bring wet hay and flakes to his lips, in small handfuls. He agrees to drink. He seems to regain possession of his body little by little but suddenly falls back into total apathy.

The vet arrives around 9 a.m. and I describe to him the temporary state of awakening that Cali had. Unfortunately, he now sees an inert horse hanging from its loins, like the day before. He examines the heart rate, which is always high, and the breathing rate, which is always forced. He leaves, asking me to keep him informed.

During the day, Cali will liven up a little, from time to time, to nibble. It is visibly painful for him to urinate and defecate, his ears droop, his eyes squint and he goes into violent spasms when he relieves himself. He is still sweating, despite the cold. The oedemas, due to the incessant infusions, reach all of its lower line. We begin our third night of watch.

Peeve, the box neighbor, also has EAM. All the horses from Cali’s pasture had a blood test to check muscle enzymes and only Peeve and Cali were affected. Peeve will regain clear urine in three days, thanks to the infusions. For Cali, it will take much longer. Cali will take 9 days to return to normal urine.

On the road to recovery

The phases of awakening and depression are spread over three days. Then, the episodes of Cali activities multiply and extend as they go. We remain hopeful and continue the infusion protocol. Cali has lost a lot of weight and has been tied down since December 17. The presence of muscle enzymes decreases very slowly in the blood test but the horse has already regained its normal heart and respiratory rhythms.

It took ten days and nine nights of non-stop watch for Cali to find clear urine. We can finally stop the infusions! On December 30, that is to say thirteen days after the discovery of the disease, I am authorized to let him go a little in his box; he moves badly, still seems very weak and his hindquarters barely respond to him. I prevent him from lying down, for fear that he will not be able to get up, and mobilize him with passive movements to solicit his proprioception. During a forced immobilization, the horse gradually loses the motor sensitivity of its body and it is recommended to make it do gentle stretching movements of the front and back legs in order to preserve as much as possible the muscles and the elasticity (at least that’s what I read in the books).

Cali unfortunately cannot bear the efforts to lie down and get up and now suffers from lesions to a tendon and to the muscle of the biceps. He must remain attached for another month and will receive an infiltration as a bonus. At this point, the vet now estimates that he will take a year to regain his basic form and, of course, we cannot comment on his sporting future.

Part 3

The assessment and the consequences of the treatment and the disease

Repeatedly administered anti-inflammatories caused ulcers. Cali was yawning, grinding her teeth and hyper salivating. So we stopped concentrate feeds and opted for alfalfa fiber, mash, carrots and unlimited hay. During her acute attacks, Cali was put under a gastric bandage, accompanied by aloe vera gel (30mL/day).

The veterinarian also advised me to supplement it with clay, a natural gastric dressing that is more permeable than those sold in pharmacies, which do not allow nutrients to pass through. Cali refused clay placed directly in his food because it turns into an unpalatable paste; on the other hand, the aloe vera has always gone down very well. Cali also suffered tendon and muscle damage to his arm (humerus) from straining to lie down and get up. He was infiltrated when he was already coming out of three weeks under general anti-inflammatories.

Peeve, Cali’s meadow mate also affected by EAM, meanwhile suffered from immunodeficiency and foot abscess; according to the farrier, this reaction is normal, the toxins being eliminated by the extremities.

Veterinary costs related to the EAM

The total amount of veterinary costs (excluding the complication of tendinitis) cumulate to approximately €1800, distributed as follows:

- 40% infusions

- 20% VAT

- 15% travel and consultations

- 15% dietary supplements and medications

- 5% blood samples

- 5% miscellaneous expenses

- 135 liters of infusions (the equivalent of around €700) will have been injected in Cali!

The reflexes that can be useful

From now on, I put in my first aid kit some Leva-Carb™, an oral syringe that contains charcoal and clay. This syringe was prescribed urgently by the veterinarian from the first moments. Leva-Carb™ neutralizes toxins in the food bolus in the event of poisoning, it is safe and can save precious hours in a similar situation.

There are many sources (notably the RESPE5, equine pathology epidemio-surveillance network) that work to prevent equine atypical myopathy and note the symptoms to watch out for. I invite you to consult them, if you haven’t already.

From now on, I will ensure to check:

- the trees surrounding my horse’s pasture, even if it has never had a case of EAM

- that my horse always has access to hay (of good quality and without samaras or seedlings), even if he is in good condition and works well

- find out about existing mutual insurance to protect my horse (and my wallet!)

Cali was able to recover from this difficult ordeal. He actually took a year to get back on his feet.

Part 4

A constructive exchange with a research veterinarian

During Cali’s convalescence, I spoke with Dr. Dominique Votion, research veterinarian, specialist in atypical myopathy and founder of the GAMA (atypical myopathy alert group), monitoring network for the EAM.

Morgane (M): I try to rehabilitate Cali by gently massaging him and making him do passive movements. We took the drip off yesterday morning and I let him go a bit in his cubicle but I don’t think he would be able to get up if he were to go to lie down (he seems to want to, but I prevent him).

Dominique Votion (DV): He must be extremely tired; if he is out of the disease, he should be able to get up on his own.

M: Last Saturday, the toxins in his blood were still not quantifiable. Why?

DV: You mean the muscle enzyme levels were still high? Only a few rare research laboratories measure the level of toxin. In any case, it will be necessary to wait for the level of muscular enzymes to return to normal to begin to very gradually put the horse back to work.

M: Do you have any advice regarding his rehabilitation? Given the low survival rate, vets don’t seem to know the proper protocol.

DV: It is true that we lack information, the survival rate being very low. There is no standard, scientifically tested protocol for returning survivors of atypical myopathy to work. Nevertheless, following a survey of twenty-three owners of survivors, I was able to gather some information.

The fitness procedure for the horses in this survey was of the same type: hand walking once or twice a day, starting with five minutes a day, then gradually increasing the duration for four to six weeks. Then the horse was lunged or remounted, gradually increasing the trot and canter time. In general, the owners report to us that two to six months were necessary to be able to work the horse normally again.

Obviously, this protocol must be adapted according to the horse. Two owners reported to us that their horse had rapid fatigue and shortness of breath during the first weeks of the protocol, so the return to work had to be even more gradual. It is necessary to do according to the capacities specific to each individual. It would be ideal for your veterinarian to follow up your horse with locomotor examinations, muscle enzyme assays and even cardiac monitoring (electrocardiography and echocardiography) within four to six weeks after the episode of atypical myopathy in order to guide you during recovery at work.

Weight loss in horses compared to the period before the disease is frequently reported. Thus, nine horses (9/23) emerged greatly emaciated from their episode of atypical myopathy. For four of them (4/9), this weight loss was transient and only lasted a few weeks or even a few months after their episode of atypical myopathy. For the five other horses (5/9 heavily emaciated), their body score was always lower (at the time of the survey) but these horses were rather fat to too fat before the disease. The majority of owners generally find their horse (19/23) similar to what it was before the disease, as if it had never been affected by atypical myopathy and therefore without apparent clinical sequelae. Four owners find their horse worse than before (4/23), two horses being calmer and less energetic; a foal has retained a delay in growth compared to another foal of his age and a sport horse has weakness in the muscle mass of the neck. Of the twenty-three horses, seventeen are working again; the others are not worked because they have not yet been broken in, are used for breeding or are retired. Among our survivors, a horse pursues an international show jumping career.